Dutch art of the 17th century has a lot to teach the film maker. During this period, Dutch painters such as Rembrandt, Jan Vermeer, Gerrit van Honthorst, Pieter de Hooch and others developed a kind of painting that combined intense realism with drama and emotion. They did this largely through a deep understanding of how lighting works within the image.

They learned from the Caravaggists, the followers of Caravaggio (the Italian painter who I’ll write about in a later post ) who was one of the first to really demonstrate how careful manipulation of light is one of the chief tools of the visual storyteller.

The film Admiral follows the visual style of the Dutch painters and the Caravaggists in using light as a way to model the physical characteristics of the films characters, to create painterly shots, and – as a self-reflexive motif that runs throughout the film – to include paintings within the films mise en scéne* to remind the viewer that the story of the film is deeply connected to the historical world which we chiefly know through the paintings . Here are some examples of how that works in the film:

Vermeer’s Milk Maid

Early on in the film we catch a very, very brief glimpse of the admiral’s maidservant working alone in the kitchen. This shot, which only lasts a couple of seconds, is a recreation of the very famous Vermeer painting The Milkmaid. The recreation of this painting in the film indicates not only a connexion with Vermeer and the Dutch Golden Age’s great achievements in art, but alludes to Vermeer’s representation of domesticity and the beauty of the everyday – which in the context of the film is the one thing that the Admiral is never able to truly experience, because he sacrifices his family life in order to save the nation.

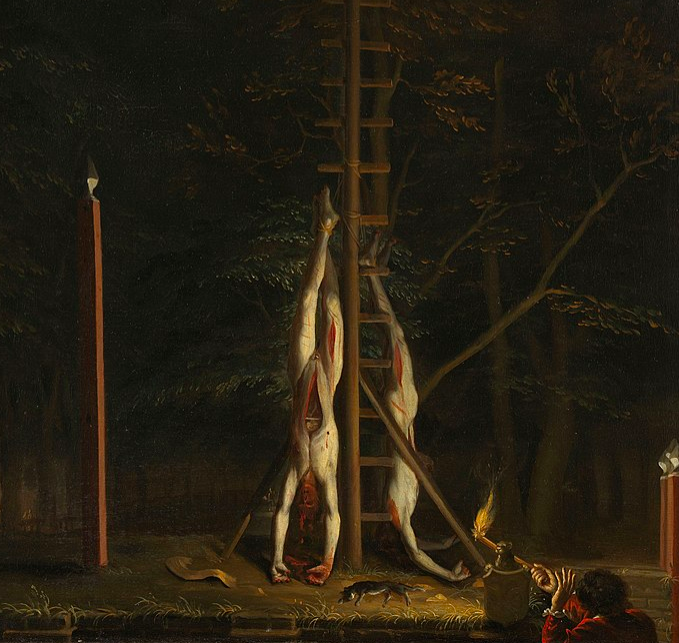

Later (and I don’t want to give away too much of the plot), there is a terrible scene where one of the main characters in the film is killed in a particularly vile way by a baying mob in the streets of Amsterdam The film shows the painting being done from life; as the characters pass through the street, we catch a glimpse of an unseen painter painting the picture. We have no idea whether or not the painting was done in situ (probably it wasn’t).

Realistic Sea Battles

In my previous blog post, I showed you the recreation of the sea battles in the film, and how they are based on the marine pictures by Dutch artists. However, what is particularly interesting is that the nature of movie-making is that you can actually go onto the ships and participate in the battles, rather than – as the painters had to – portray them at a distance. Roel Reiné’s camera brings us right onto the deck in the middle of the fighting.

At one point we are taken below deck and the lighting of this particular shot is strongly reminiscent of a painting by the Caravaggist Spanish painter Jusepe de Ribera (see below, Ribera’s St Jerome, a good example of the lighting effect).

It is a technique known as tenebrism which is very extreme contrasts of dark and light. This is an important shot because it really brings home to the viewer the human experience of the battle, the terror that the participants must have felt, yet at the same time, the framing of the picture gives us a sense of something spiritual – perhaps the worthiness of the sacrifice.

* mise en scéne is a term that refers to everything that appears in the frame of a shot: what is before the camera and its arrangement: composition, the set/location and all its props, the actors and where they are placed, the costumes, and the lighting. It can also include the use of colour and tonality. The term originated in the theatre and means ‘placing on the stage’. In film, of course, there isn’t a stage; the camera substitutes for the stage. The camera is much more mobile and so the mise en scéne of a film is constantly changing

to learn more about Art History and film, read my book ART HISTORY FOR FILMMAKERS

and you can order it from your local bookstore