Eugène Delacroix paints the revolution of 1830 and establishes a Romantic visual idea of revolution that has had a lasting influence on art, film and culture.

“Although I may not have fought for my country, at least I shall have painted for her,” Delacroix wrote in a letter to his brother.

The revolution is well underway: the people are fighting in the streets. We see cannon smoke and in the distance, building are on fire. The rabble swarms over the bodies of the dead: soldier and citizen alike are fallen. The crowd exults, the violence is inescapable, and all are led by the majestic figure of Lady Liberty, urging on her crowd of citizen soldiers. Exhilarating stuff!

This is one of the first actively political works of modern painting.

It depicts the Paris uprising of July 1830, which overthrew Charles X, the king who was restored after Napoleon’s defeat. Delacroix did not participate in the uprising: he was in the Louvre helping to protect the collection from the chaos. Though he depended on commissions from institutions and members of the royal family, Delacroix had republican sympathies. Perceived the uprising as a suitable modern subject for a painting, he started to paint this dramatic scene of the crowd breaking through the barricades, led by the female symbol of Republican France, “Marianne” or Lady Liberty. It is a cinematic and Romantic vision, seeking to achieve an immediate emotional impact.

The painting has a pyramid composition: the base, strewn with corpses, serves as a pedestal supporting the the victors as they push forward, and the pyramid is crested by the lovely Marianne.

In her figure, Delacroix combines classicism, Romanticism and realism. Liberty’s dress is draped in a classic manner, and her face has a Grecian profile with a classical straight nose. The bare-breasted, fierce image of Marianne leading the battle had appeared in the French revolutionary propaganda of the 1790s, and Delacroix revives it, but here makes it romantic, full of colour and life, yet also real.

Eugène Delacroix paints Realism

Her upraised arm reveals underarm hair. Underarm hair was considered to be so vulgar that no painter dared to represent it.

She holds a real gun in her left hand, the 1816 model infantry gun with a bayonet.

The other figures in the painting are both as real and as symbolic as Marianne. Delacroix has faithfully reproduced the style of dress worn by different sectors of the society at the time.

The man to the right of Liberty in the black beret (worn by students) is a symbol of youthful revolt. The man with the sabre on the far left is a factory worker. Elsewhere in the picture, we can see that Delacroix has depicted other workers and peasants realistically. The figure with the top hat may be a self-portrait or one of Delacroix’s friends. He represents a bourgeois or fashionable urbanite making common cause with the ordinary people.

The painting was a key inspiration for Eve Stewart, production designer for the 2012 film of Les Miserables which is set during the 1830 events.

Eugène Delacroix paints a dangerous picture

The 1830 uprising did not end in a new Republic, but in a substitute King, and it took several more revolutionary events before France finally became a republic. As one of the most dramatic, persuasive and stimulating images of revolutionary action, Liberty Leading The People was dangerous. The painting was hidden away from public view in 1863. Today it is one of the most popular paintings in the Louvre.

Liberty Leading The People is one of the most cinematic paintings of the 19th century and continues to serve as a matrix for crowd scenes, and for the inclusion of symbolic character types within the composition.

Delacroix’s Liberty is bare-breasted to emphasize her femaleness, but her female body is not sexualized here. This active, heroic, female figure owes something to the athletic dynamism of the Roman goddess Diana.

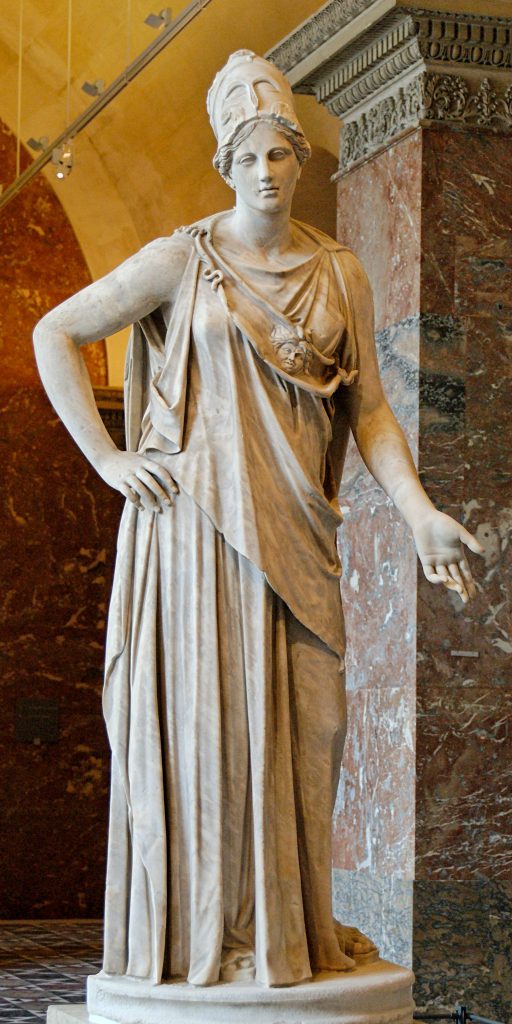

Diana (L) and Athena (R)

Artemis with a hind, better known as “Diana of Versailles”. Marble, Roman artwork, Imperial Era (1st-2nd centuries CE). Found in Italy

But Diana was a goddess of chastity and was not supposed to be sexual. Likewise, Athena, goddess of wisdom as well as of strategic warfare, is not sexual but is one of the ‘virgin goddesses’ (together with Diana/Artemis and Hestia).

Active female heroes that are NOT sexual are rarely presented in cinema

In recent years female action heroes have become more common, but with the exceptions of ‘Sarah Connor’ in the Terminator films and ‘Ripley’ in the Alien films, it is rare to see female action heroes who are not sexualized.