Dramatic journalism?

I’m going to start with art critic Charles Baudelaire’s quip about painter Horace Vernet. Writing in in The Painter of Modern Life in 1863, Baudelaire accuses Vernet of being ‘a veritable journalist, not an artist’. Baudelaire criticised Vernet’s paintings of recent history as being too accurate, rejecting Vernet’s work as reportage rather than art since ‘he just paints what he sees’. Baudelaire believed that art should be truthful but imaginative.

Baudelaire wanted artists to paint modern life, and to find the grand and the epic in it. It is no wonder then, that he championed Delacroix’s imaginative vision of the barricades rather than Vernet’s observational one. Delacroix stayed painting in his studio in the 1830’s uprising, while Vernet went out to see, and draw, the violent insurrections of 1848.

Journalism and Baader Meinhof Complex

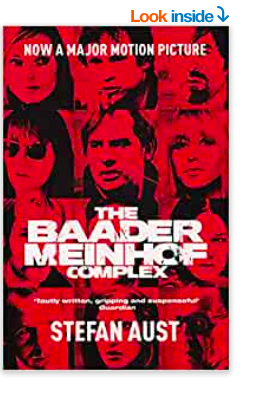

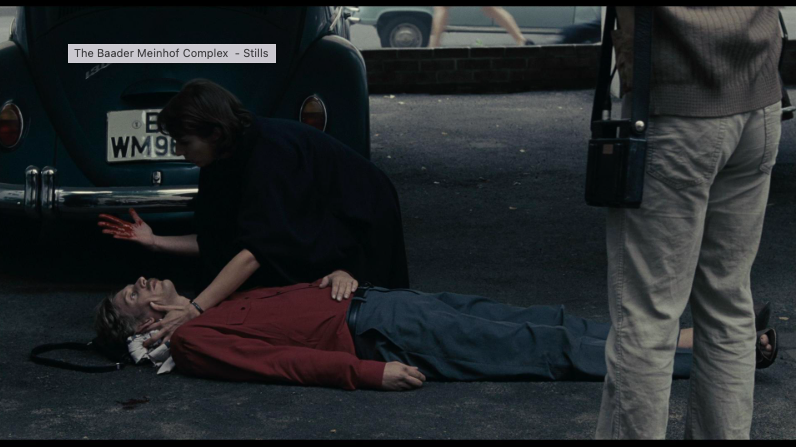

Uli Edel’s Baader-Meinhof Complex chronicles the Red Army Faction in 1960s and 70s Germany, events that happened during his youth. The Baader-Meinhof Complex is a straightforward adaption of journalist Stefan Aust’s factual book of the same name. Aust, who knew several RAF members and has been a journalist since that time, has done extensive research on the subject and wrote a first draft of the script. Producer Bernd Eichinger and Uli Edel finished Aust’s screenplay.

The film is an example of high realism and devotion to historical accuracy. However, the film’s pacing resembles that of the thriller genre, and Edel employs stylistic visual approaches that may be called ‘painterly’.

The Red Army Faction (RAF) committed bank robberies, bombings, kidnappings, and assassinations. The film follows Ulrike Meinhof, Andreas Baader, and Gudrun Ensslin from their formation to their capture and deaths at Stammheim jail. The film attempts to be a factual yet dramatic recounting of a still-contentious and divisive recent history.

At the time of the events shown in the film, Stefan Aust was a colleague of Ulrike Meinhof at the magazine her husband edited. Aust is therefore both an investigative journalist and an inside witness to the early stages of Meinhof’s radicalization. The film faithfully follows the timeline of Aust’s book, from Meinhof’s criticism of the Shah of Iran’s visit to Berlin on 2 June 1967 and the subsequent violence up to the 18 October 1977 deaths of Baader and Ensslin in prison. Aust did not only research and investigate the events, but he was also a direct witness to many of them. Possibly because of his links to the German left at the time, he obtained many candid interviews with former members of the RAF, reflecting on their actions and motivations.

Truth and Accuracy

The Baader-Meinhof Complex is based solely on investigative journalism, unlike other more fictionalised accounts. The film’s judgements are mostly agreed upon by experts, and all the characters are real. It is important to understand the film’s relationship to the facts, and how the journalistic approach and the dramatic approach cohere. Yet the film is no mere recitation of facts. It operates on the viewer emotionally, through scenes which adhere faithfully to the factual account but are visually presented as thrilling and, at times, sublime.

This unusual factual thriller does not trade historical accuracy for drama.

Writer-producer Bernd Eichinger stressed that he is not interested in the why but the how of the RAF, which lets the deeds speak for themselves and offers multiple interpretations. Edel and Eichinger achieve this by combining both ‘art’ and ‘journalism’ approaches, through an engagement with painterly visuals as much as through detailed attention to authenticity.

Director Edel and DP Rainer Haussman adapt art historical images into the mise en scene, suffusing the realism of the journalistic adaptation with a sense of the sublime. They create moments that ‘evoke’ paintings.

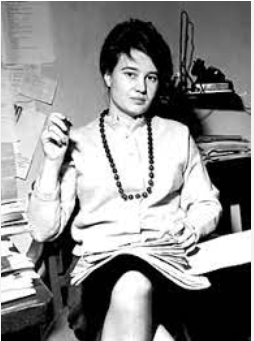

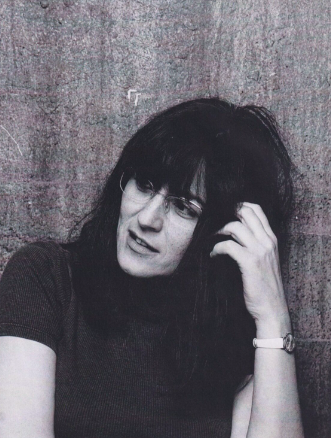

Ulrike Meinhof

The Baader Meinhof Complex is a film about a journalist. Although the film is ostensibly about a group, for much of the narrative it principally follows Ulrike Meinhof’s gradual transformation from a left-wing journalist into an active, armed radical of the Red Army Faction.

The film mainly follows Meinhof’s radicalization and introduces Andreas Baader and Gudrun Ensslin, who are less important in the story. The first part of the RAF story—radicalization, violence, and capture—is exciting. The rest of the story involves their detention, dramatic trial, and mysterious deaths in prison.

Aust’s research shows that the thriller approach is terrifyingly appropriate for the first half of the film. ‘Baader arranged it so our heroic political beliefs flew right out of the window, and there we were, right in the heart of a thriller,’ said Beate Sturm, a former member. “You just slip into that sort of thing,” Sturm said about joining the RAF. Once in, the group had momentum. ‘As we felt we knew we got into all this for the correct political reasons, we relished the thrill of it too,’ Sturm says to Aust.

However, the actions of historical individuals (and what drives them) is something that cannot really be subjected to the rigours of ‘authenticity’; even the diaries of Meinhof, mined by Aust and Edel, cannot simply be replicated on the screen. It is left to the visual design to convince the viewer that what they see is ‘true’.

Painting adaptation

The most striking aspect of the film is not simply its desire for visual historical authenticity and the methods used to achieve it, but the visual structure of the film. Edel and Haussman’s attention to period authenticity binds the two parts of the film stylistically, but once the characters arrive in Stammheim, the pace slows and the contrast between physical and psychological violence becomes stark. However, the first portion’s dramatic and well realised set-pieces capture the audience and prepare them for the second part.

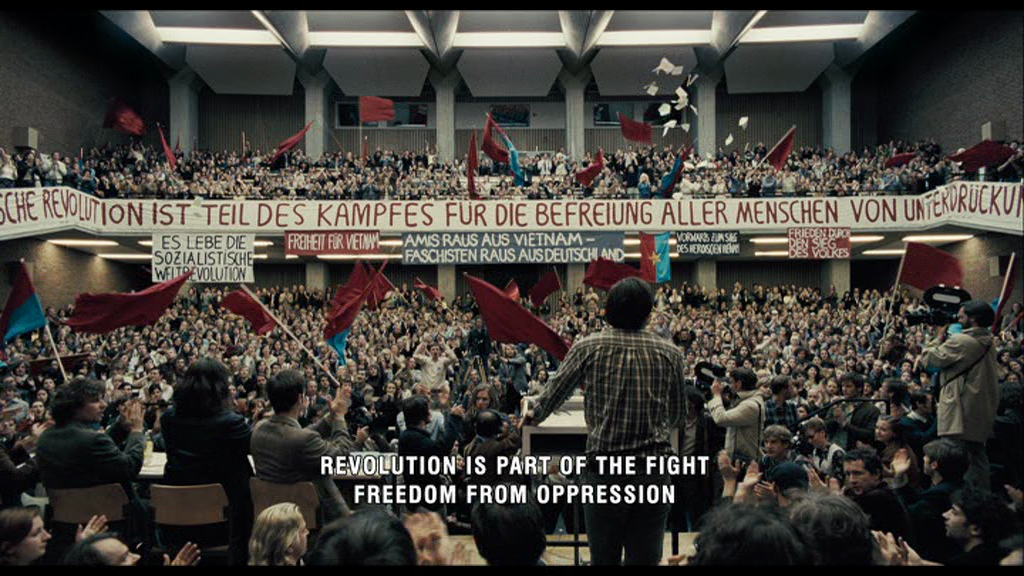

The main set-pieces are visually spectacular, fast-paced, and audio-visually impactful. The first is reenacting the 2 June 1967 protest against the Shah of Iran’s visit to Berlin. Second is student leader Rudi Dutschke’s speech at a Berlin University rally against the Vietnam War. The third is the mass protest at the Axel Springer publishing company in Kochstrasse, 11 April 1968, following the attempted assassination of Dutschke.

Tragic Emotion

Edel calls the RAF a “German tragedy”. Tragedies evoke strong emotions. Edel says in an interview, ‘I don’t think you can grasp anything at all until you can understand it emotionally. ‘I don’t believe in a purely rational analysis of things. I believe that a purely rational analysis must always be supported by an emotional analysis as well’.

This sense of tragedy is conveyed less through the story, which in its journalistic form is fairly grubby and complicated, than through its visual reference points. By faithfully re-creating the historical event while increasing the emotional charge of the scene, culminating in a moment meant to evoke the sublime to transport the viewer emotionally the film moves from journalistic realism to painterly grandeur.

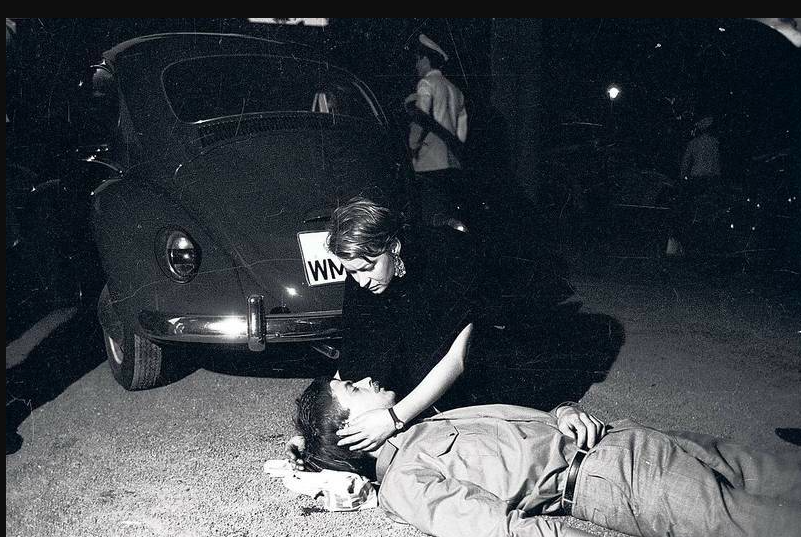

2 June 1967 The Bismarckstrasse riot reenactment.

First AC Astrid Meigel said four cameras were used on Bismarckstrasse, ouside the German Opera House, to capture the demonstration’s violence and panic: one held-held, two Steadicams, and one studio camera on a dolly. DP Klaussman says, ‘we wanted to get specific images that have appeared on the original news coverage of the event. You have to start with the big shots, with everybody there, and then you move closer and closer until you’re getting little moments like the young girl being crushed against the barrier.’ The constantly moving, eye-level camera makes the viewer feel viscerally frightened. All cameras are at victim eye level. We run alongside young and elderly people alike, see them smashed in the face. However, news footage of the events shows a big discrepancy between what the fiction film audience sees and what the news cameras filmed. Klausmann’s cameras are always “inside” the action, beaten and trampled by police, unlike the news cameras which stand back like Vernet’s observation of the barricades. Finally, one of the protestors is shot dead. In short, the scene is shocking and distressing: state violence wreaked upon unarmed civilians.

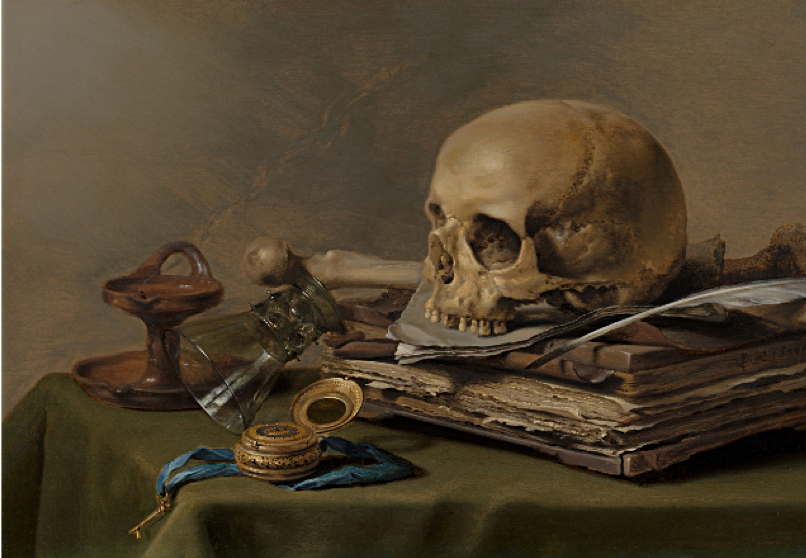

The Baader Meinhof Complex depicts the 2 June 1967 as a “massacre of the innocents,” one of the most potent themes in art history. Flemish painters turned the New Testament tale of the Massacre Of The Innocents into a horrific condemnation of state brutality against civilian populations. Pieter Bruegel, Peter Paul Rubens, and Cornelis Van Haarlem are three of the most striking painters of the topic. Their images show state aggression against unarmed civilians.

Peter Paul Rubens’ version immerses the viewer. Dead babies are piled up as living ones are brutally manhandled. A soldier lifts an infant as if to smash him into the ground. One woman holds the soldier’s sword blade and bites his hand, while another scratches his face. It’s a horrifying vision of state violence breaking families apart, yet it shows women fiercely fighting back. The image astonishes modern viewers. The Biblical “massacre of innocents” depicts state aggression, seen in the Roman soldier’s helmet at the upper part of the picture. It’s a depiction of horrible brutality, visceral assault of women and children, injustice, and pathos.

Meinhof Crosses the line

After Rudolf Dutschke was shot in April 1968, the Axel Springer publishers were attacked across West Germany. Springer denounced students and young people, and the students denounced Springer and all its publications. Many blamed Axel Springer for the assassination attempt. West-Berlin publishing house headquarters saw some 3,000 protesters. They chanted, lit fires, and tossed stones and Molotov cocktails. In the film, Meinhof becomes involved, instead of observing like a journalist. The scene shows her ‘crossing the line’ from observer to participant.

Religion

The media footage of the event shows the protesters gathering in daylight giving speeches and massing in great numbers but but Edel shows Meinhof arriving in the evening after the fires have been started. The effect then is of a highly dramatic chiaroscuro, so different to the televisual images. Footage from other West German cities where Springer officers were attacked do show nighttime images but as you can see they tend to depict the authorities more than the perpetrators. Edel’s vision was quite different: he wanted to show the rioters’ perspective.. In order to do this, he unsurprisingly turns to Delacroix rather than Vernet.

The third example I’ll show you comes from same scene but offers an entirely different viewpoint on the RAF story and invokes a different kind of artwork.

Like a scene from Hieronymus Bosch’s Hell, the demonstrators’ bonfires shadow everything against the night sky. Meinhof stands silently, taking in the commotion and frenzy around her. Bathing in the chaos and frenzy all around her, a growing euphoria is clear upon her face.

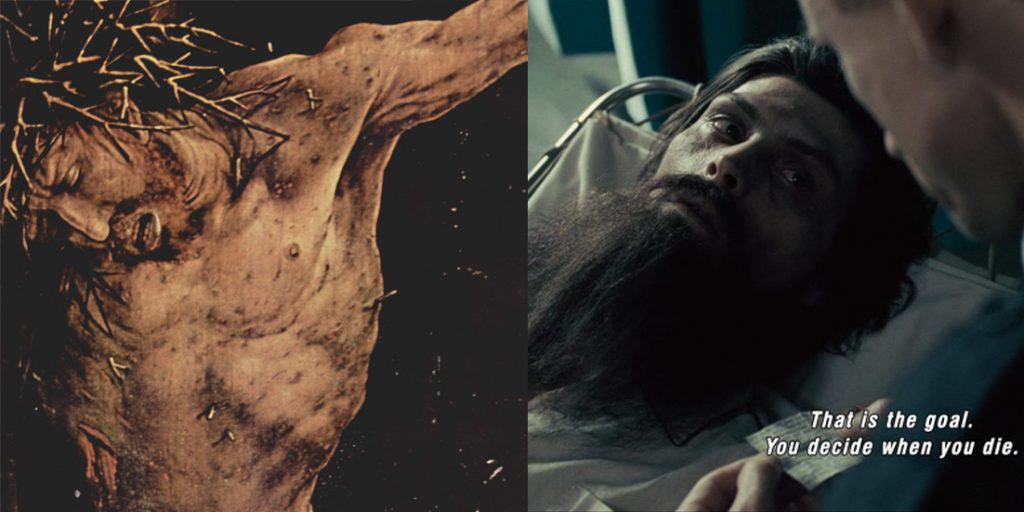

She is then grabbed and dragged to the police cars. As she moves out of the frame, someone shouts. The camera pans over a hellish wasteland of turned-up cobbles, strewn newspapers, and burning delivery vehicles. A bearded, bare-chested young man with long dark hair stands, holding his arms out in a crucifixion pose amid the commotion. The camera comes in for a medium close-up as he stands Christ-like, silhouetted against the fires, shouting “Dresden! Hiroshima! Vietnam!”

The scene’s end, with the Christlike figure howling in the flames, cannot be compared to be situated in relation to Delacroix’s revolutionary heroics. We must look to older works from an earlier worldview. In fact, this figure seems confusing because the film doesn’t show any theological standpoint.

If the Springer riot is Meinhof’s own moment of ‘holy self-realisation’, the later prison scene shows the starvation death of RAF member Holger Meins as skeletal, tortured features of Grunewald’s Christ in the Isenheim altarpiece.

What is the meaning of these quasi-religious references?

The 1978 film Germany in Autumn interviews RAF member Horst Mahler in prison. He discusses “evil” and personal responsibility in dissident groups. He asks ‘how is it that a person like Ulrike Meinhof is willing to kill, or at least accept it as a possibility?’ … ‘moral degeneration of the capitalist system’ is completely apparent, and those who act within it do so in a corrupt manner, ‘we judge them morally, condemn them, and, based on this moral judgment, we recognise them as evil’. Mahler concludes ‘Therefore it is justified to destroy it as evil, even if it is in human form. In other words, killing people’.

Stefan Aust observes that ‘for me, the whole struggle from the very beginning of my research was realising that the RAF had a quasi-religious character more than a rational political character’. Therefore, by framing the revolutionary cause as a Christ-like self sacrifice, to deliver us from evil, Edel gets right to the heart of how the radicals saw themselves. For all their talk of freeing themselves from the shackles of the historical past, and joining in with the oppressed of the world for new internationalist world socialism, they remained culturally embedded in the Judeo-Christian mindset with which they were brought up. Because they resisted evil, the RAF convinced themselves they were good. Because the RAF was good, their opponents were evil.

Using the visual references to the massacre of the innocents and to the suffering Christ – images embedded in Western art and therefore in the Western worldview – in the context of a violent riot and the hunger-striking prisoner, Edel offers a visual manifestation of what Horst Mahler articulates: the theological worldview of the modern revolutionist.

Conclusion

To sum up, the realist style is still dominant in each set-piece and carries on throughout the film. But in the set-pieces, we see realism move toward the sublime, in the depiction of the terror of violence, and in the Springer scene, catharsis. Each of these scenes visually maps onto an existing visual motif in painting, and each of the paintings communicates something about contemporary events. Moreover, each painting manipulates the mise en scène in order to indicate something of the sublime: the terrifying violence of the massacre fo the innocents paintings, Delacroix’s romantic exhilaration of revolutionary direct action.

The Baader-Meinhof Complex’ high-concept ‘the RAF story as a thriller’ adapts the journalistic text faithfully, then reaches beyond it, locating the emotional and artistic impulses within the film’s mise en scène.

Though faithfully following Aust’s journalistic account, and adhering to both the newsgathering images and the published histories on the subject, Edel’s film manages to combine the exactitude of the ‘veritable journalist’ and the intensity sought by Baudelaire’s idea of ‘plunging’ into the world. The film blends correctness and authenticity with drama and affective engagement. This tension between the faithful recounting of ‘what happened’ and the desire for imaginative and interpretive drama through the invocation of the sublime, is at the heart of The Baader Meinhof Complex.

Is the film ‘realistic’? Yes it is. It follows, more than most films, the established facts and accepted judgements.

Is it ‘real’? That is impossible to judge. No film can recreate the past. Every person that remembers the time – including the producer and director – will remember it differently. The ‘real’ is always temptingly out of reach. We can only imagine, and tell stories.

©GillianMcIver2023