Strongly influenced by visual art, Vampyr is a work of startling beauty and maddening mystery; it is a vampire film like no other

A final version of this essay appears in The Palgrave Handbook of Vampires, ed. Simon Bacon, Palgrave McMillan 2024.

“Imagine that we are sitting in an ordinary room. Suddenly we are told that there is a corpse behind the door. In an instant the room we are sitting in is completely altered; everything in it has taken on another look; the light, and the atmosphere have changed, though they are physically the same. This is because we have changed, and the objects are as we conceive them. That is the effect I want to get in my film”

Carl Theodor Dreyer

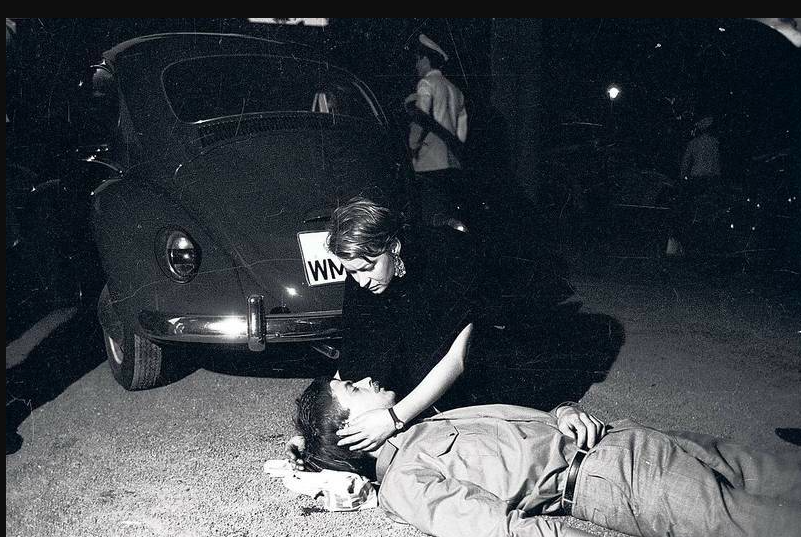

It’s surprising that filmmaker Carl Theodor Dreyer (1889–1968) made a vampire flick, or any horror film for that matter. Before directing Vampyr, the Danish filmmaker had directed the silent 1928 picture La Passion of Jeanne d’Arc, a riveting portrayal of the trial and execution of the French female fighter. The groundbreaking lighting and extreme close-ups achieved by cinematographer Rudolph Maté in that picture, which is based on the transcripts of Jeanne’s trial, are noteworthy. So why did Dreyer, who was known for his spare but powerful dramatic films, decide to make a genre picture with Vampyr in 1932? Keep in mind that Dreyer wasn’t merely cashing in on the vampire film trend; he shot Vampyr on his own in France at the same time that Tod Browning was filming Dracula for Universal Studios. Therefore, Dreyer’s film was distinctly his own, even though he may have been influenced by Browning and others. The film’s star, Vampyr, footed the bill solo, with no backing from studios or industry insiders. Even though he was an acting novice, Baron Nicolas de Gunzburg agreed to finance the film if he appeared in it (as “Julian West”). Dreyer, Rudolph Maté, and the rest of the production team discovered a partially abandoned mansion in the Parisian village of Courtempierre with a meagre budget that could only afford two professional actors. This mansion and its environs served as their setting. The set was a dark, foreboding, and dilapidated building, which the actors and crew said added to the mood that director Dreyer and cinematographer Maté were going for.

The Plot

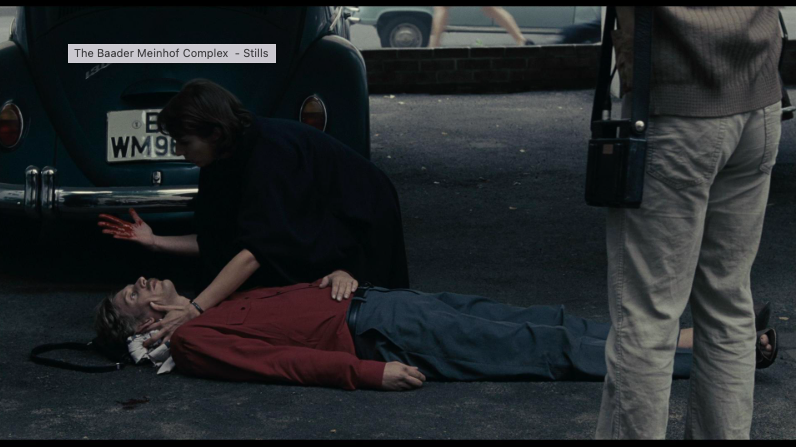

The Vampyr story is odd but straightforward: at dusk, aimless wanderer and passionate devotee of the occult Allan Grey arrives in a village . Grey leaves his hotel room after hearing guttural mutterings and sees a blind, disfigured man. Soon an angry man bursts into the room and hands him a box . Curious, Grey goes out into the “eerie moonlit night” in search of the man. Moving shadows terrify him. After following shadows, he sees an harsh old woman in a mostly abandoned building. He watches a malformed soldier’s shadow wander while several bodyless couples dance to a fiddler’s lively melody. Grey follows phantom beings to a decrepit manor estate and witnesses the lord shot dead. While helping the grieving Leone and Gisele, the deceased’s daughters, Grey enters a demi-world of terrifying sights. While waiting for the coachman to return with the police, Grey inspects his father’s gift. A vampire book is inside. Gisele sees Leone in the garden, and the creepy old woman hunches over her prone body as Grey and Gisele approach: she is the vampyr! The murdered coachman’s body returns with the coach, and no police. Leone is suddenly overcome by bloodlust and nearly attacks her sister. A strange doctor arrives and arouses suspicion – we see he is actually the vampyr accomplice.

Grey experiences some terrifying lucid dreams that feel real. Rallying, Grey and the servant stab the vampyr in her grave. Leone is released – breathes her last and says, ‘My spirit is free’ but dies instantly. Grey saves Gisele and they leave the village by crossing the river. The doctor rushes to a nearby mill to escape but the servant activates the mill and suffocates the doctor with flour.

A haunted world

‘The people in [Vampyr] glide slowly through a vague, whitish mist like drowned men …. the film is pervaded by nightmare obsession, and it shows a deadsure, calculated use of every means at [Dreyer’s) disposal’

Dreyer’s friend, writer Ebbe Neergard

Languid, slow, sometimes moving like a sleepwalker, the hero Allan Grey (as played by Nicolas de Gunzburg) is a good-looking, well-dressed young man who wanders into the haunted world of Courtempierre. In the first intertitle we are told that ‘This is the story of the strange adventures of young Allan Gray, who immersed himself in the study of devil worship and vampires. Preoccupied with superstition of centuries past, he became a dreamer for whom the line between the real and the supernatural became blurred.’ Grey is a dreamer, already obsessed with the occult. To say Grey is wandering the countryside looking for vampires may be going too far, but his curiosity is amply rewarded when he finds Marguerite Chopin. There are other clues that Grey is not quite ordinary. According to Alex Barrett, de Gunzberg’s ‘sullenly stiff performance only enhances the character’s strangeness.’ (Barrett 2022) Dreyer uses the amateur actor’s limitations to create an affectless protagonist, who undergoes the most harrowing of experiences maintaining a fascinated yet calm demeanor. Indeed the character may be experiencing nothing more than a dream, as the film’s English title Vampyr: The Dream of Allan Gray implies.

The character drifts into somnolence several times. At the start of the film he goes to bed and is woken by the father. Is what we see next a dream? Certainly Grey keeps falling asleep then is roused into another nightmare. After giving his blood for transfusion to Leone, Grey dreams of a skull, then a skeletal hand clutching a vial of poison. He is awakened by the Old Servant, and rushes into Leone’s room in time to push the doctor out of the way and snatch the vial of poison from the girl’s hand. Chasing the doctor outside he falls, weakened by blood loss; the fall causes him to limp to the garden bench where he falls asleep.

This third slumber offers Dreyer’s most startling and iconic shot: the figure of Grey rises from his sleeping self and embodies a translucent, insubstantial self which moves away. This spectral Grey passes towards us to an empty stone doorway and finds himself is again in the disused building of the earlier scene. A coffin stands, draped on a sheet, nearby is its glass-topped lid. Ripping the sheet away from the coffin, Grey sees the corpse: it is himself. From overhead we see Grey lean down over his dead self. The coffin moves: it is being carried by unseen hands. The vampire peers into the coffin, looking directly at him. The spectral Grey, a sentient corpse, embarks upon ‘the most audacious concept in film history: the corpse’s a view of his journey to the grave’.

Amateur actor Rena Mandel, playing Gisele, also moves like a sleepwalker, though she has an almost permanent expression of huge-eyed fright. She is the story’s fair, innocent, passive ingenue, witness to her sister’s agony and her father’s death. At the end of the tale, she escapes the village with Grey and though it is implied that they are now a couple, there is no hint of a romance throughout the story. As David Rudkin points out, Grey and (especially) Gisele are not fully characterized, nor do they conventionally find each other and fall in love.

The Old Servant, sometimes referred to as Joseph (Albert Bras) has an unexpectedly significant role in the story. It is he whom, taking up the book where Gray left off, understands the nature of the vampire, and is the one who takes decisive action. While Grey is largely passive in the film, the manservant is active: it is he who goes forth to seek the vampire’s grave, where he is joined by Gray. Joseph brings the tools and instigates the destruction of the vampire. However, it is Grey who wields the hammer, the camera ‘framed on the head of the iron shaft stroke by stroke descends with it as it is hammered down into the corpse.’ As he does so, Chopin expires, transforming into a skeleton. It could be argued that, in terms of action, the Old Servant is the actual hero of the story. He delivers the doctor’s final punishment, burying the servitor in a bright white avalanche of flour. As played by Bras, the character is phlegmatic, and carries out his tasks as if they are routine. He is resolute and decisive and does not give in to fear or panic.

Sybille Schmitz, the only experienced film actor in the project, plays Leone. The character needed a subtle actor who could indicate strong feelings and compulsions in a very short sequence. First, we see Leone in bed, very weak and semi-aware of her condition. Schmitz’s ability to convey Leone’s agony elicits the viewer’s sympathy. Saved from the vampire, Leone expresses a wish to die; her suicide is exactly what the vampire wants, and why it gives the vial of poison to the doctor. The moment of pity is then turned to horror when Leone’s expression changes, she is consumed with bloodlust. This is Schmidt’s key scene: Leone feels the urge and, turning her head with a horrible smile, fixates upon her beloved sister Gisele. However, she is too weak to attack. In that brief moment, (in extreme closeup, reminiscent of the shots in La Passion de Jeanne d’Arc) we see the true horror and agony of the vampire’s victim.

The Doctor (Jan Hieronimko) serves his vampire mistress with enthusiasm. Unlike the other servitors he is not a shadow or a simple minion. He continues to live as the village doctor although, as Gisele notices, he only comes at night. Grey has seen the doctor earlier, and is slightly suspicious, but is persuaded to donate his blood to save Leone. The Old Servant works out what is going on, crying ‘something terrible is happening!’ which awakens Grey and starts the second part of the film: the quest to find and destroy the vampire. They realize the doctor’s complicity and he flees. However, although there is no scene where he takes Giselle captive, we realize that he has done so, presumably to serve as Chopin’s next meal. The Doctor is, in a sense, the most ordinary of the characters, as he appears little affected by the goings-on. He lights his cigar nonchalantly with the candle as he supervises the soldier nailing Grey’s coffin shut. Nevertheless, he is the most active of the two villains, and so it is satisfying when he meets his gruesome end in a deluge of flour.

The other servitors include the (uncredited soldier) with the wooden leg, and the shadows that seem to obey Chopin. The soldier’s shadow separates from his body to wreak the vampire’s command; the other shadows are entirely disembodied. Apart from being a very clever operation of location camera work, the shadows belong to the film’s eerie nightmare world, where much is left unexplained.

The Vampyr herself

Mme Marguerite Chopin (Henriette Gérard) is horrible, but has none of the doctor’s insouciant air. She is a grim, solid, heavy presence but seldom appears in the film. She has no ‘vampiric’ characteristics, no fangs or Gothic trappings. She looks like an old French bourgeoise, which is what she was in life. But she refuses to stay dead. At her initial appearance, commanding the shadows to ‘Stop!’ she resembles a strict grandmother. Rena Mandel said that Dreyer showed her reproductions of Goya’s work and indicated that was the atmosphere he was looking for. While nothing in the mise en scene replicates a Goya painting or print, Chopin resembles the witchy crones in some of Goya’s prints, those from the ‘Witches and Old Women’ Album of 1819-23 for example. As art critic Jonathan Jones describes them, ‘that mixture of death and life is at the root of the horror that creeps up on you bit by bit. The horror is not just some Gothic schlock. It is a painfully true recognition of corruption, decay and dying’. He notes that Goya’s witches ‘bodies are round and plump like children painted by Bruegel, but their faces give away the deadly truth’.

The revelation that a vampire is afoot and that the undead creature is the old woman, is finally recognized just after the midpoint of the narrative. We might expect to learn more about Mme Chopin, or witness a confrontation between her and Grey, but nothing of the sort happens. So what can we make of Chopin as a character? It is not clear exactly what era she originally lived in. However, the gravestone above her corpse is well weathered, so we can conjecture that the vampire has appeared periodically over time. This is also indicated by the book Grey receives from the father. Still, one noticeable thing is that the vampire does not benefit much from her blood feasting. She remains very old, slow, disabled. She needs the doctor’s support to move about, and finally, she is blind. In short, Chopin is barely alive, but stubbornly clinging on to life. What she wants even more than blood is authority and influence, even over shadows.

The rotund and almost grandmotherly appearance of Chopin hides her ghoulish nature. But did she have another inspiration beyond art? Some critics have noted Dreyer’s unhappy childhood: given up for adoption at birth, he was taken from the orphanage by an unloving couple. In his own adult life Dreyer came to demonize his foster parents and especially his foster mother. Was shethe model for Marguerite Chopin?

Chopin’s ravaging of Leonie is age preying on youth; the desiccated, crippled crone feeds on the young and beautiful woman, rendering her almost lifeless. This vampire is a cruel, devouring, problematic mother figure. Peter Swaab suggests that Vampyr is a story ‘about an older generation cruelly prolonging itself by preying on the young. The vampire and doctor are like an old married couple in which the tyrannical wife dominates. The servant Joseph and his wife are benign elders to counter these nightmare parents’. (Swaab 2009, 62) It is notable that the vampire does not threaten to bite Allan, but seeks to consume the young women. Leonie, who has been made a half-vampire, looks with lust at her sister Gisele, marked as the next victim, whom the doctor subsequently captures as an offering to his vampire mistress.

Old age preying on youth reminds us of the lost generation of 1914. Is it too much to link the film to the idea of the old condemning a generation to die on the battlefields of Flanders? Was this still a notion by 1932? Is this the meaning of the decrepit, disabled soldier? There does not seem to be any other reason to make the doctor’s helper a soldier. This ruined being, who is most active when he is a shadow, is a diametric contrast to the lithe, well-presented Allan Grey. But Grey, like Gunzburg, would have been far too young to fight in the First World War. Still, the decrepit relics of the war generation were still all around Europe. Either way, the soldier is being used by the old vampire, as is the young and lovely Leone.

However, the plot and even the characters of Vampyr are less significant than the film’s visual style, which can be described as a recreation of a waking dream.

The art of Vampyr

Vampyr captures the essence of a truly unsettling nightmare. Dreyer delves into the mysteries of the waking world, revealing the spiritual forces at play beneath the surface of our everyday reality. This challenges our perception of a purely rational and predictable world governed by natural laws.

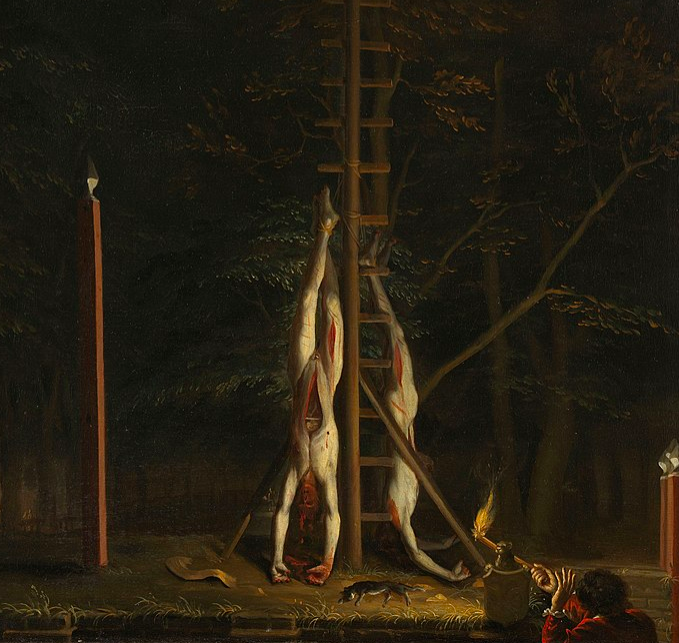

Dreyer, and his cinematographer may have been inspired by a range of artists and art works. According to Dreyer’s former colleague, writer Henry Hellsen, Dreyer used a number of well-known paintings to set up many of his shots. The old man with the scythe, the first truly creepy and unsettling image in the film, is strongly reminiscent of Jean-François Millet’s ‘Death and the Woodcutter’ (1859) which, held in Copenhagen’s Glyptothek, was familiar to Dreyer. Hellsen goes on to associate the penultimate shot, of Grey and Gisele walking through a glade in the morning light, with Corot’s 1861 ‘Orpheus and Eurydice Leaving the Underworld’, which Dreyer may have seen in reproduction. (Olson and Collier 2014)

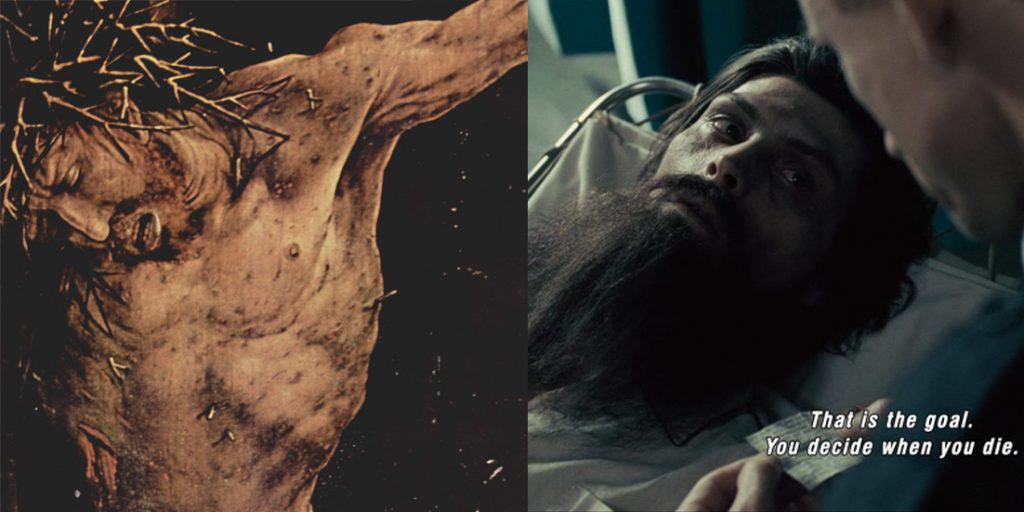

But if Vampyr is a film about sleep and dreams as much as it is about bloodsucking, what are Dreyer’s artistic influences? Visual art depictions of the dream and the dreamer range from Raphael’s ‘Dream of Jacob’ (1518) to Henry Fuesli’s ‘Night Mare’ (1781). ‘Night Mare’ is one of the key pictures that supplied Dreyer with the imagery for Leone’s supine figure, draped in white, with the malevolent crone squatting over her. Closer to Dreyer’s era, the Symbolist painters – active in Central Europe and Scandinavia – were likewise concerned with dreams and dream-states. Finally, as mentioned, Dreyer was interested enough in Goya’s works to show them to Rena Mandel. Goya’s well-known print ‘The Sleep of Reason Produces Monsters’ from Los Caprichos (1797-99) suggests that, in the battle between light and shadow, the daytime world ordered by reason gives way to the night and its demonic creatures of shadows.

Dreams and dreamscapes

Vampyr was an attempt to depict, through the medium of a waking dream, the idea that the terrible does not reside in the external world but in our own minds. Nothing can stop us from going overboard when we’re excited about something, and our imaginations have no bounds when it comes to the objects around us. (Swaab 2009, 60) Dreyer

“The irony is that viewers have grown accustomed to seeing film sets that any real location looks out of place, which is exactly my goal” Dreyer

Although Dreyer had a lifelong fascination with psychological reality, it in no way limited his films to realism. Whatever the case may be, approaches to realism in film have evolved through the years and throughout countries. (pp. 53–66 in McIver’s Art History for Filmmakers (2016). In Vampyr, the bourgeois solidity of the vampire, the protagonist’s contemporary attire, and the inn and house’s utter ordinariness all contribute to the film’s reality. All of the settings in Vampyr were actual sites. The director’s obsession with realistic detail was later detailed by Eliane Tayara, Dreyer’s assistant: the crew had to collect, feed, and place a lot of spiders to spin their webs in the right areas; he wanted the semi-derelict house of the vampire’s helpers packed with actual cobwebs. Dreyer was adamant that every bone be genuine, and that the skeletal hand that Grey saw in her dream holding the poison bottle had to be a female skeleton.

Using the camera to show us nonexistent things like Grey’s multiple ethereal forms, the disembodied shadows, and the spirit of the father who died by the window, Maté went beyond the actual. In keeping with the era, we can discern some Freudian imagery that Dreyer utilised in Vampyr, even though Freudian psychology does not play a significant role in the film. Chopin, the vampire, is more earthy than otherworldly; she moves slowly and clumsily while leaning on a stick. Additionally, she commands the shadows by rapping on the wall with the stick. Just like her, Grey arrives in the village with a stick—this time, a lightweight fishing pole. Since it serves no purpose, it gets thrown away before long. Nevertheless, in their last showdown, the docile man brandishes his weapon—a stake—and drives it into the vampire’s flesh.

At this juncture, Grey takes the initiative to save Gisele, claiming her as his own and escorting her out of the hamlet and across the river. Candlelight illuminates numerous sequences in the picture; nevertheless, it is clear that the candles do not provide the illumination; rather, the scenes are typically illuminated by a diffused light that is both bright and foggy, creating an atmosphere that is neither night nor day. A spooky, mysterious air is added to the video by the flickering, otherworldly aspect of the candles. In a similar vein, numerous scenes are engulfed in a fantastic fog created by Dreyer and Maté’s method of filming with a covering of gauze over the lens. Everything we observe is mediated by this filter.

With the lighting in Vampyr, it’s hard to tell where you are or what you’re looking at. In most outside scenes, such as Grey crossing a field or Marguerite Chopin crouching over Leone, the heavy fog makes it nearly hard to see their features due to the obliteration of light. Dreyer takes this concept a step further by expanding it with semi-transparent surfaces that sit between the camera and the characters. at his vision, Grey passes many windows: the one at the inn’s bar, the one in the chateau’s parlour with its shutters and veining, the one in the room where Gisele is held hostage, and lastly, the one on Grey’s coffin, which has a glass plate. The image is obscured to varied degrees by each of these windows due to their individual refractive effects.

Like the fog that finally engulfs the fleeing lovers, the sifting powder that engulfs the doctor at the mill has a similar textural density. Also, the camera impacts the film’s spatial links; yet, Maté’s camerawork isn’t doing a good job of establishing the narrative’s causal chain. For example, “at least five times the camera moves away from a figure and glides off on its own, dwelling on atmospheric elements and giving short shrift to the cardinal story point.” Maté and Dreyer’s mastery at highlighting the camera’s active role in constructing and challenging cinematic space is one of the film’s distinguishing features.

Conclusion

Vampyr exudes an air of foreboding, however it is not overly terrifying. Through “acts of magic” displaying the “invisible world,” Dreyer accomplishes what Cocteau characterised as “creating a world that is superimposed upon the visible and to make visible a world that is ordinarily invisible” in Vampyr.

Rather than being about vampires, Vampyr explores the gap between reality and perception. In both our own and the film’s worlds, Dreyer wants us to go deeper than what meets the eye and challenge the veracity of our first impressions. Every viewing of the film is unique, thus it’s best to watch it multiple times. Viewers who have seen Vampyr before will be taken back to the village of Courtempierre and Grey’s nightmare and have a new experience. Revisiting the event gives one a deeper understanding and admiration for the work of Dreyer and Maté.

![Giorgione - Three_Philosophers [Google_Art_Project]](http://arthistoryfilm.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/Giorgione_-_Three_Philosophers_-_Google_Art_Project-300x255.jpg)