History in Art and Film

Today’s painting depicts a moment in Colonial History The Battle of Aboukir which happened in Egypt during the war between Napoleonic France and Britain. The history of what happened is explained below. This painting by Antoine-Jean Gros Bataille d’Aboukir, 25 Juillet 1799 is in the Palais de Versailles.

The picture shows the successful charge by General Joachim Murat at Aboukir. The general is on the white horse in the centre of the composition. In fact Murat himself commissioned Gros to make the painting in 1806. It was brought to Versailles, hung in the Coronation room, in 1835.

This is a good example of a ‘cinematic’ painting. Let’s consider the elements of what makes a painting ‘cinematic’

Let’s start with LIGHTING

Notice how the central part of the picture is much brighter and ‘lit’ even though this is supposed to be taking place outdoors in ‘natural’ light. The sense of brightness is created by the placement of white things in the centre of the picture, rather than any suggestion of a change in the natural lighting. This is a good example of the painter Antoine-Jean Gros’s fidelity to realism, within the context of a highly dramatic setting and action.

COLOUR

Gros uses three main colours in this picture; yellow, red and white. Yellow (shades from yellow to brown) is the colour of nature – the dust and earth of Egypt. White appears in the clothing of some of the figures, but in the main, it is the colour of the General’s horse that stands out. Red is very dominant; redness forms a circle around all the centre whiteness. it’s a striking effect.

MOVEMENT

Paintings can’t move, but the ‘cinematic’ painting very often gives the illusion of movement, usually through the gestures of the figures or through the use of dynamic composition such as strong diagonals horizontals and verticals that indicate that something is moving through space. Even though we don’t see it moving, we can easily understand that it is moving. When we look at paintings such as this one we really get to see the dynamism of movement as a painted illusion. Here movement is indicated in the centre of the painting by the diagonal positioning of the standard, which slices through this section of the painting in a very strong diagonal line. It is also red, which almost gives it a sense of being like a sword slash, through the painting. The gestures of the figures, with outreaching arms and the twist of the bodies, also indicates movement. The whole painting feels as though it is vibrating with movement, writhing and alive.

Cinema Battles

This kind of highly dramatic realism is very common in cinema. In art history, painting something so that it looks as though it is really there or really happening, is often referred to as ‘naturalism’. The struggle and the figures look natural even though as a depiction of the actual battle of Aboukir, I’d seriously question how ‘realistic’ it actually is. I mean, why would the man at the feet of General Murat’s horse be stark naked? It’s really unlikely the Ottoman troops would go into battle stark naked or wearing clothes that fall off really easily. As a depiction of Colonial History, the Battle of Aboukir may not be realistic but it is spirited.

However, from a dramatic point of view, it allows the painter to demonstrate the vulnerability of the Ottoman soldiers (and the weakness of their position) overcome by the magnificent French troops under Napoleon’s great general, Murat. Additionally, it allows Gros to show off his ability to paint the human figure. Of course, if we were to try to re-create this battle for cinema we really couldn’t get away with showing this nudity, not for decency reasons but because it would actually be completely ridiculous. In fact, even in this picture, it’s completely ridiculous but somehow painting gets away with it.

The depiction of battles in cinema has a long history and has produced some extremely interesting scenes in films but these scenes are difficult to shoot. Partly because unlike in painting, is difficult to get single compositions within the frame so that one can focus on specific incidents. However, painting is a good guide for the filmmaker. Lighting, compositions use of colour and gesture in paintings can inspire the filmmaker because it demonstrates very clearly what is effective and engaging to the eye.

Some great battles in cinema history:

Omaha Beach Saving Private Ryan

The Street Protest Turned Battle, The Baader-Meinhof Complex

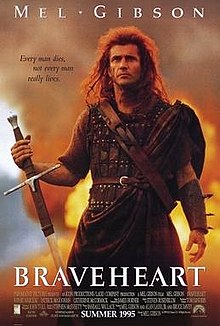

Braveheart – The Battle Of Falkirk

Apocalypse Now, Helicopter Beach Assault

Waterloo (1970), The Charge Of The Cuirassiers

Gladiator, Battle In Germania

Glory (1989), The Storming of Fort Wagner

Zulu (1964), The Battle of Rourke’s Drift

The History

What Actually Happened at Aboukir?

There were several battles called Battle of Aboukir (or Abu Qir) during the period of war between Napoleon’s France and Great Britain.

You may be familiar with the battle of Trafalgar which is commemorated in London’s Trafalgar Square, although Trafalgar itself is in Spain You may be familiar with the battle of Waterloo which is commemorated in Britain by a railway station and a bridge and is also the name of a town in Ontario, Canada – as well as a number of towns in the English speaking world. But the actual Waterloo is in Belgium.

The point is, often we understand history through particular moments but we don’t understand how those moments arrived. How on earth did the French and the Turks and later the British end up having a fight at a place with an obviously non-European name like Abu Qir?

Where is Aboukir?

Abou Qir is in Egypt; you can go there*: it’s a town on the Mediterranean coast near the ruins of ancient Canopus 23 kilometers northeast of Alexandria. It is located on a peninsula, with Abu Qir Bay to the east. The bay is where, on 1 August 1798, Horatio Nelson fought the Battle of the Nile, often referred to as the “Battle of Aboukir Bay”, an event also painted by Philip James De Loutherbourg (1800) among others.

The battle depicted by Gros took place a year later on land between the French expeditionary army and the Turks under Mustapha Pasha (acting as an ally and agent of the British, though the Ottomans later switched sides). The French claimed it as a victory but it didn’t resolve anything.

Two years later they fought the Battle of Alexandria (aka Battle of Canope), on 21 March 1801 between the French army under General Menou and the British expeditionary army under Sir Ralph Abercromby, who died in the battle . after this the British marched on Alexandria and laid siege to the city.

*I’ve been very near to it but didnt actually make it there. Next time!

Colonialism depicted

There are no paintings of the siege of Alexandria, or what happened in this essentially civilian city. Alexandria was one of the most important cities in the eastern Mediterranean. There’s no record left by Europeans of the suffering that happened to Egyptians as a result of being caught in the crossfire between two European empires and the dying, opportunistic Turkish empire.

As you can see there’s something very uncomfortable and disconcerting about the idea of British and French and Turkish armies battling it out on Egyptian soil.

What is interesting about Gros’s painting is that, for all its attempt to depict the excitement of battle and the man on the White Horse as a symbol of European domination, when you know the actual history, the painting becomes a testament to the brutality of the colonial project, whether it’s English, French or Ottoman. It’s a very honest picture of what was at the root of colonialism: violence. A testament to real Colonial History The Battle of Aboukir is an important painting and we shouldn’t forget about it.

If you want to see more of Colonial History the Battle of Aboukir by Antoine-Jean Gros [Bataille d’Aboukir, 25 Juillet 1799] is in the Palais de Versailles.

Note: the colonisation of Egypt

Europeans were very aware of Egypt and regularly train traded with this outpost of the Ottoman Empire. Egypt had not been an independent country since the Roman conquest and by the 18th century was firmly established as a very lucrative, revenue-giving province of the Ottoman Empire. The French had considered trying to get hold of Egypt for over 100 years but the expedition that sailed under Napoleon Bonaparte in 1798 was connected with revolutionary France’s war against Britain. Napoleon hoped that, by occupying Egypt, he would damage British trade with the East Indies and strengthen his hand in bargaining. But he had other aims. He wanted to free Egypt from the Ottomans and establish it as a progressive territory of Revolutionary France, Egypt was to be regenerated and would regain its ancient prosperity. Together with his military and naval forces, Napoleon sent a commission of scholars and scientists to investigate and report the past and present condition of the country.

Adieu Bonaparte

The story of Napoleon’s occupation of Egypt is told very sensitively and dramatically in the film Adieu Bonaparte by the Egyptian film maker Yousseff Chahine. The great actor Michel Piccoli plays one of the French scientist-engineers sent by Napoleon (who appears in the film played by Patrice Chereau) and his relationship with Ali, a young Egyptian man caught between traditional culture and his resentment at the reality of colonialism, and his fascination with European science. The film is available in French and Arabic .

WRITTEN BY GILLIAN MCIVER, 2017 CREATIVE COMMONS LICENSE Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International

SOME RIGHTS RESERVED YOU MAY SHARE, REPRODUCE, DISTRIBUTE, DISPLAY, AND MAKE ADAPTATIONS SO LONG AS YOU ATTRIBUTE IT TO GILLIAN MCIVER.

GILLIAN MCIVER IS THE AUTHOR OF ART HISTORY FOR FILMMAKERS (BLOOMSBURY PRESS) 2016 AVAILABLE AT ALL GOOD BOOKSELLERS INCLUDING AMAZON AND THE REST