Django Unchained 2012

The western was the film genre that

brought the heroic figure together

with the overwhelming yet splendid

landscape. This case study looks at

a subversion of that cinema genre

through an unlikely relationship:

English portrait and landscape

painter Thomas Gainsborough

(Blue Boy, 1770) and American

filmmaker Quentin Tarantino (Django

Unchained, 2012).

Quentin Tarantino has often

been referred to as the archetypal

“postmodern” filmmaker. His films

bear the hallmarks associated

with postmodernist approaches:

appropriation of ideas, images,

and texts from different sources;

referencing other movies, books, and

art; pastiching established genres;

conflating popular culture and high

culture. In his later films, Tarantino

subverts existing genres, including

established trash and schlock genre

forms, and through the process of

subversion seeks to make a serious

point.

Thomas Gainsborough, the

eighteenth-century portrait and

landscape painter, could not be

further apart from Quentin Tarantino

at first glance. Yet Gainsborough

was subversive in many ways. Like

Tarantino, he broke new artistic

ground and challenged established

artistic forms. However, until Django

Unchained, it would have been

ridiculous to imagine a comparison

between Gainsborough and

Tarantino, or even to discuss them

within the same sentence. But in that

film, Tarantino and his design team

(J. Michael Riva and Sharen Davis)

appropriate a key element of one of

Gainsborough’s most popular and

most widely distributed painting,

The Blue Boy. It is from this starting

point that we will look at this case

study of Django Unchained and

Gainsborough’s Blue Boy.

The Blue Boy was painted before

Gainsborough moved to London.

Born and raised in a lower-middleclass

family in rural Suffolk, he

moved to the spa town of Bath as

his portrait practice developed.

The problem for Gainsborough was

that he preferred landscapes. He

liked painting people—skin tones,

drapery, and costume—but, with the

exception of certain female clients,

he disliked painting portraits of the

type of people who commissioned

him. We know this because in his

letters he complains about his rich,

arrogant, empty-headed clients, and

says many times over that he wishes

he could just go to the countryside

and spend the rest of his life painting

landscapes and common folk. (His

own favorite was The Woodsman,

1788, a portrait of a poor forest

worker.)

It is not unusual for people

to dislike their day job and wish

to be doing something else. But

Gainsborough’s ability to create real

likenesses of his subjects made him

successful. He rejected the current

fashion of painting his subjects

dressed up as mythological beings;

he wanted to paint people in their

own clothes, looking as they would if

you met them. One of the trendiest

fashions in mid-eighteenth-century

England was to be painted wearing

the court costume of the previous

century, in the style of Dutch painter

Anthony Van Dyke at the court of

King Charles I. Van Dyke’s paintings

were widely copied; all decent

painters understood that they should

be able to make a Van Dyke to order.

Van Dyke painted his aristocratic

subjects wearing elaborate silk and

lace suits, one of the most influential

being Lord John Stuart and His

Brother, Lord Bernard Stuart (1638).

In the painting, Bernard Stuart is

wearing a fabulous pale blue satin

suit, though most of it is obscured by

a heavy silver cape.

Normally this is the kind of

portrait that Gainsborough would

have scoffed at replicating. But

two years previously he had been

elected a founder member of the

Royal Academy of Arts. It was never

an easy relationship; Gainsborough

felt like an outsider with something

to prove. He decided to challenge

the claim of the Academy’s head, Sir

Joshua Reynolds, that blue colors

should be used only as accents, not

in the main mass of the picture. He

painted a mass of blue, an exercise

in color and light reflecting on

silk, using layers of different blue

pigments: lapis and indigo, cobalt

and turquoise, together with charcoal

and creamy white, and sent The

Blue Boy to the Royal Academy’s

1770 Salon.

But who was the blue

boy? He was not an aristocrat or

theater celebrity who would normally

command an Academy-level portrait.

He was Jonathan Buttall, a good

friend of Gainsborough and an iron

merchant in London. It was not a

commissioned portrait: Buttall posed

for Gainsborough as a friend. Buttall

was far outside the circles of power;

he could never have worn court

dress. Therefore, The Blue Boy is a

subversion. It is not only a painting

of an eighteenth-century man in

seventeenth-century dress; it is an

aristocratic portrait that portrays a

middle-class man.

The painting became the talk of

the Academy, and its success spurred

the painter to move to London two

years later. He was commissioned

by the royal family, and his success

enabled him to take more time out

to paint his beloved landscapes.

But it was not that simple. Soon after

arriving in London, Gainsborough

fell out with the Royal Academy and

spent the rest of his life in rivalry with

Joshua Reynolds. He would probably be

surprised to know that The Blue

Boy remains his most popular and

most influential painting—though

not his best—while to him, it was

a caprice. While Jonathan is not

portrayed heroically, he stands

for the bourgeoisie, excluded at

that time from political power and

influence, which was still in the hands

of the aristocracy. Dressing him in

Van Dyke costume must have been a

bit of a joke, a subversion to slip into

the heart of the Establishment, the

Royal Academy.

By the late nineteenth century,

The Blue Boy was an internationally

popular print and is said to have

inspired the 1919 film Knabe in Blau

by F. W. Murnau (now thought to

have been lost). Quentin Tarantino

and costume designer Sharen Davis

likely first came in contact with

the picture as a kitsch print; it was

ubiquitous throughout the 1970s,

appearing in many inexpensively

printed versions. Blueboy was also

the name of a US gay porn magazine

of the 1970s.

Tarantino, like Gainsborough,

started as a rank outsider. He has

talked many times about his lack

of any insider connections to the

movie business, his total lack of

power or influence when he started

his career. It was hard. “Pauline Kael

used to say that Hollywood is the

only town where people ‘can die

of encouragement’ and that kind

of was my situation,”5 he says.

Like Gainsborough, Tarantino has to date

shown no intention of following an

established career path. Despite his

love of popular culture, he has not

made a studio franchise picture.

He regularly takes a drubbing from

critics, who decry his unabashed

love of trash cinema, and those who

criticize his films for violence.

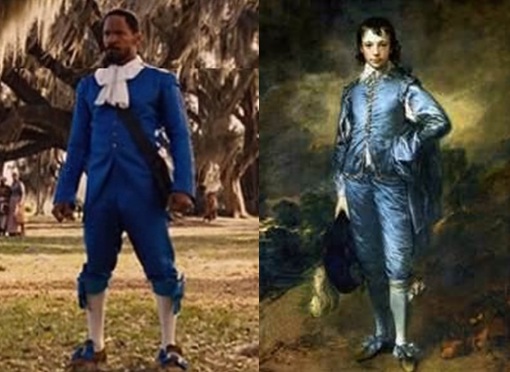

Django Unchained is in part a

road movie; as production designer

Michael Riva says, it is Django’s

psychological journey, but it is also

a geographical journey through

landscape. Django and Schulz

arrive in Tennessee and head to

a haberdashery, where Django is

invited to pick out a costume in order

to play the part of Schulz’s valet.

The next shot is of Django wearing

a bright blue suit, styled in a vague

pastiche of seventeenth-century

fashion, the archetypal Blue Boy.

The connotations are rife: The Blue

Boy is a well-known kitsch print, but

the painting resides in the important

Huntingdon Museum in Los Angeles.

“Boy” was a condescending term

used to address all African American

males regardless of age, particularly

in the South.

We first see Django in his blue

suit from the side, riding a horse

through a landscape, a cotton field.

The composition of this shot is

itself a nod to the subgenre of the

equestrian portrait.

Van Dyke made a

famous equestrian portrait of King Charles

I, which was repeatedly copied, and

Gainsborough made variations on

Van Dyke (as exercises, or simply to

pay the bills). And the David portrait

of Napoleon is an equestrian portrait.

Equestrian connotes aristocrat and

hero. But in that costume? Not yet.

The blue suit makes Django stand

out, command attention, and is

ineffably striking. Riva notes that

“color is a really important to me,

it’s a mood establisher.”7 The intense

blue (much brighter than The Blue

Boy’s silk) acts paradoxically as a

red flag to the white supremacists

he encounters. But both Jonathan

Buttall and Django are in costume;

Jonathan could never dress like that

to do his daily business as an iron

dealer. Django soon equips himself

in what Riva calls “warm nicotine

colors,” in more practical—and

stereotypically “western”—garb.

The Blue Boy motif is incongruous

in a western. Yet, as Tarantino

points out, “One of the things

that’s interesting about Westerns in

particular is there’s no other genre

that reflects the decade that they

were made and the morals and the

feelings of Americans during that

decade than Westerns. Westerns

are always a magnifying glass as far

as that’s concerned.” He notes that

“Westerns of the ’50s definitely have

an Eisenhower birth of suburbia and

plentiful times aspect to them. . . . the

late ’60s has a very Vietnam vibe to

the Westerns leading into the ’70s,

and by the mid-70s, you know, most

of the Westerns literally could be

called Watergate Westerns because

it was about a disillusionment and

tearing down the myths that we

have spent so much time building

up.”

Django is a western that

subverts the dominant white male

hero in a wish fulfillment revenge

fantasy that forces the audience

to confront race and slavery. It is

probably too much to consider The

Blue Boy as a wish fulfillment class

fantasy. Perhaps we should consider

Django Unchained’s Blue Boy motif

to be a parody, with its political

connotations, while Gainsborough’s

Blue Boy is an apolitical pastiche.

Yet Gainsborough’s own letters bear

witness to his private discomfort with

the upper class.

Tarantino and Gainsborough share

the status of being both insider and

outsider. Neither man belonged to an

influential coterie or was a member

of an art or film dynasty. Both gained

success on their own terms, even if

Gainsborough sometimes whined

about his clients.

You don’t actually need to

know anything about the Van

Dyck paintings or Gainsborough

to appreciate Django Unchained.

But understanding the art historical

provenance of the costume, with its

many underlying connotations, can

help you see why it is so effective,

and how art can be so influential

that it manages to be replicated in

unexpected places, while continuing

its original message.

![Giorgione - Three_Philosophers [Google_Art_Project]](http://arthistoryfilm.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/Giorgione_-_Three_Philosophers_-_Google_Art_Project-300x255.jpg)