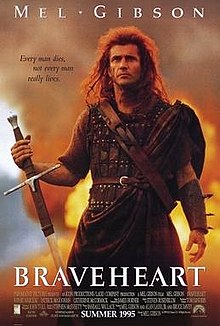

Heroic stories – whether true or mythical, are enduringly popular. This heavily fictionalized biopic of William Wallace, who led a Scottish rebellion against the English King Edward I, was a critical and box office success, winning Oscars for Best Picture and Best Director – in all, a total of five Oscars.

The ideal “hero” model was established in earliest antiquity, in the ancient epics of Gilgamesh, the Iliad, and the Norse sagas. Joseph Campbell in his book The Hero with 1000 Faces shows that similar stories of heroism are present in all societies, at all times in history. It is not a surprise to see that from early times artists have sought to portray heroes and heroic acts. Heroes in paintings are not meant to be realistic; they are heroic. What about heroes in films?

The old-fashioned notion of hero was taken up immediately by cinema, particularly during Hollywood’s Golden age. The appeal of the heroic character endures: some of the most popular include Indiana Jones, Ripley in the Alien films and Neo in the Matrix films. Neo’s partner in The Matrix, Trinity, performs a role similar to the Greek goddesses who help (and often become lovers with) heroes like Odysseus, Perseus and others. Trinity also has elements of the powerful goddess Diana the Huntress (Greek Artemis), a popular subject in Graeco-Roman sculpture. Wearing a tunic and carrying weapons, Diana seems quite dangerous (see the Diana of Versailles from 200 AD in the Louvre). But later paintings tend to show her nude and sexualised (e.g. Titian’s Diana and Actaeon, 1556).

This well known painting of Napoleon by Jacques-Louis David is a famous depiction of more recent heroism.

Apparently Napoleon actually crossed the Alps on mule, a far more suitable animal for this kind of tricky and difficult journey. However this wouldn’t do for heroic painting, and so David has portrayed the general not only on a horse, but on a splendid horse rearing up on the edge of a precipice. The staunch general maintains his composure, looking directly out of the canvas and pointing upwards, towards victory and triumph. In the background the Army pushes forward: we can see the war machines being transported up the side of the mountain, and the tricoleur in the lower right. The structure in the picture is striking: Bonaparte is centre and is upright, while the horse and the mountain are on a strong diagonal running from the top left to the bottom right. This arrangements creates a string sense of drama and danger. The diagonal arrangement in the painting that immediately catches the eye. The sensation of wind coming from the rear is shown in both the billowing cape, and also the mane and tail of the horse, indicating the harsh alpine winds that confront the Army. Yet look at the wind direction: these winds are themselves propelling the general, the horse and the Army forward towards victory. David is indicating that even the gods are behind Bonaparte.

David was a staunch supporter of the French Revolution, even its most extreme faction. However when Napoleon took control, David switched allegiances. One might think that David would be disgraced after the fall of Napoleon, but in fact the restored King Louis 18th offered to keep David on as court painter. The artist refused, remaining true to his revolutionary principles.

David was not the first artist to show that portraying real-life people as heroes involves exaggeration and theatricality. David knew that this is not how Napoleon crossed the Alps, but he understood that in order to create a painting with the highest impact to deliver the propaganda message of Napoleon’s overarching genius, strength, power and glamour, it was necessary to create a powerful, glamorous painting. This problem is at the heart of bio-pics which attempt to show the core character in a heroic light. Much of the true story and extraneous detail has to be removed, and any act or gesture made by the central character needs to be reinterpreted as heroic. One of the best examples of this in recent cinema is Mel Gibson’s 1995 film Braveheart, which puts a completely new gloss on the true story of William Wallace. Wallace was a real person, who did rebel but under circumstances rather different to those shown in the film. The film tries to capture historical detail, but there’s no question that it was glamorized for dramatic effect

Films about Napoleon Bonaparte – how ‘heroic’ is he?

Napoleon 1927 Directed by Abel Gance DP Jules Kruger, one of the greatest history films, owing much to both David and Delaroche.

Désirée 1954 Directed by Henry Koster, DP Milton R. Krasner. This film takes a different approach and focuses upon the relationship between Bonaparte (Marlon Brando) and Désirée Clary (Jean Simmons).

Waterloo 1970 Directed by Sergei Bondarchuk DP Armando Nannuzzi (Napoleon played by Rod Steiger)

Youssef Chahine’s Adieu Bonaparte depicts Napoleon (Patrice Chereau) from the point of view of a young Egyptian during the French conquest and occupation of Egypt. In Fench and Arabic – no English versions available.

I have not really said anything about ‘superheroes’ in this article – I have been focusing more on real people portrayed as heroes. I’ll come back ot the topic of hero and superhero in the fantasy genre.