Body horror is based on deep-seated fear of the disfigurement and despoliation of the living body, and of the decomposition of the dead body. It reminds us of our mortality, frailty, and vulnerability. Ancient cultures understood this fear very well; for example, in ancient Egypt it was believed that despoiling a body meant that the soul could not reach the afterlife. Likewise, to disfigure a statue was a grave insult to whomever it represented. Body horror in art and cinema is based on the visual representation of this violence toward the body; to varying degrees, the shock is in witnessing the desecration of the living or the dead.

One of the earliest horrific images in Western art is actually a crucifixion scene: Matthias Grünewald’s crucifixion for the Isenheim altarpiece (1512– 1516). It is a night-time scene, with the crucified body in the front and centre of the composition. Grünewald’s Christ is a macabre figure, distorted in agony, his body already decaying as he slowly dies a monstrous, torturous death.

This is a painting about the extremes of physical suffering, yet it was not painted to terrify its viewers. It was painted for a hospital, and it was meant to help people suffering from plague: by identifying their own suffering bodies with the suffering of the Savior, it was meant to bring hope, if not in this life then in the afterlife. Very few representations of the crucifixion since Grünewald’s have been so graphic.

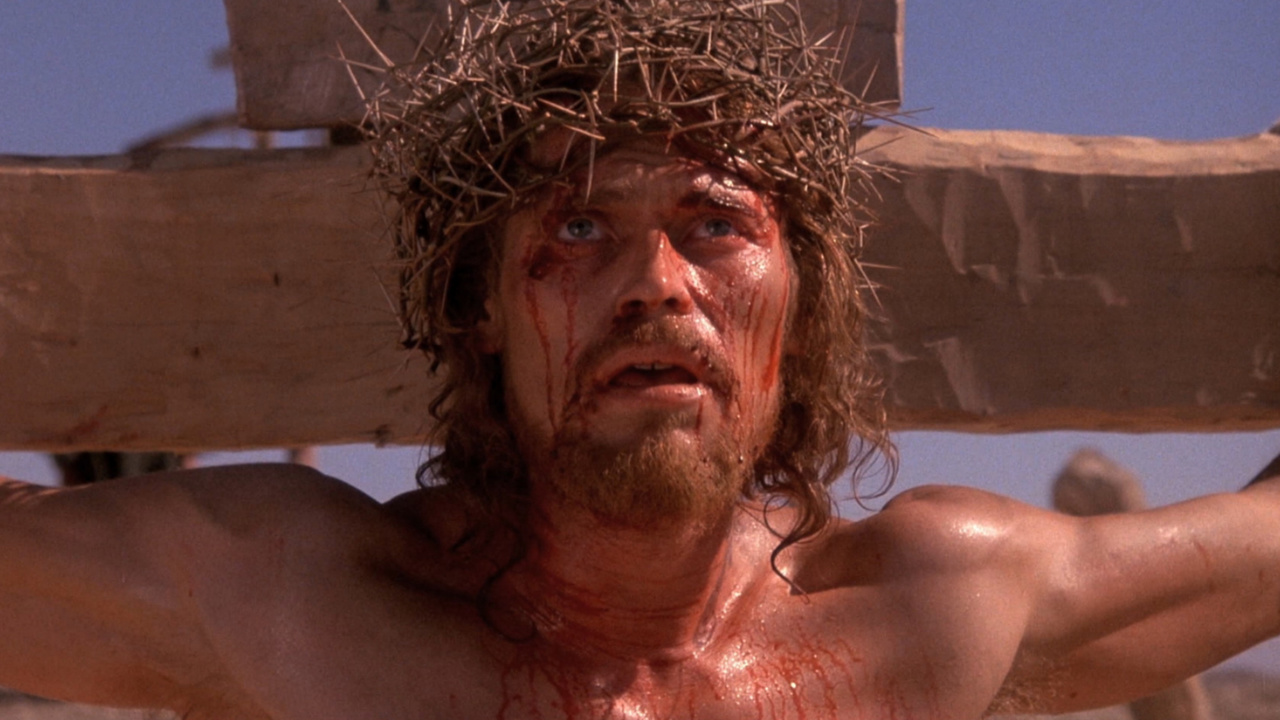

Martin Scorsese also emphasized the brutality of crucifixion in The Last Temptation of Christ (1988). Mel Gibson’s 2004 film The Passion of the Christ was controversial because of the extreme violence of the crucifixion, and there were accusations that it turned the story into a kind of body horror. This raises the question: when does extreme violence turn into body horror? It is a matter of degree, but we can call it body horror when the principal emphasis of the picture or the film is on the torn and mutilated body.

This is certainly the case in Titian’s The Punishment of Marsyas (c. 1570). According to the legend, Marsyas was a satyr (a half-human, half-animal creature) who challenged the god Apollo to a music contest and lost.

The punishment, for his hubris in challenging a god, was to be flayed alive. Titian (1488–1576) paints the flaying as a kind of diabolical party. This is not the only painting of this horrible punishment; the subject was also addressed by José de Ribera (1637), also quite a disturbing image. In Ribera’s picture, the animalistic aspects of the satyr are almost completely imperceptible. The horror lies in the visceral depiction of Marsyas screaming in agony as Apollo strips open his leg. Bartolomeo Manfred’s Apollo and Marsyas (1616–1620) is tame by comparison. In Titian’s version there’s quite a crowd, playing music and seemingly enjoying themselves. Marsyas is upside down, like an animal at slaughter, but also maybe an alchemical reference to the symbol of the Hanged Man. The mundane reality of the dog lapping up the spilt blood, while another character is collecting the blood in a bucket, like a butcher going to make blood pudding, renders the scene both prosaic and repulsive in the same moment. Yet perhaps this is another alchemical reference.

Why would artists want to paint something as horrifying as somebody being flayed alive? Titian and Ribera did not paint these pictures just for the gore. In classical times, Marsyas was always ambiguous. He was the mortal, subhuman creature who dared to challenge a god, thus upsetting the hierarchy and deserving of punishment. However, to the Romans, he was sometimes portrayed as a proponent of free speech and a symbol of liberty, and was associated with the common people. Sometimes he was even seen as a subversive symbol in opposition to the emperor. It is possible that in late Renaissance Italy, this Roman interpretation of the mythological character of Marsyas still had currency.

There are scenes of violence in paintings that would be considered too extreme for cinema audiences. However, in 2008, Martyrs, directed by Pascal Laugier, featured the protagonist Anna (Morjana Alaoui) being flayed alive in graphic detail. The film, part of the movement known as New French Extremity, continues to be controversial. However, so-called New French Extremity is only one direction in body horror cinema. Some filmmakers, such as Catherine Breillat, have been widely acclaimed for combining body horror with philosophical and intellectual questions. The same can be said, in a more populist way, about the work of David Cronenberg. Cronenberg’s earliest films, including The Brood (1979), Videodrome (1983), and The Fly (1986), are all masterpieces of the body horror genre.

In 2005, Eli Roth made the first Hostel film, which deeply divided critics, unsure if it was “just one damn blow-torching after another”10 or “splatter with a conscience.”This type of film has sometimes come to be known as ‘torture porn’. In 2010, A Serbian Film (Srđan Spasojević) was released, though almost immediately banned in many countries. The film follows a down-on-his-luck former porn actor who agrees to make one more movie, which turns out to be a snuff film; it features graphic depictions of necrophilia, rape, all kinds of torture, and child sexual abuse. Though it completely unimpressed critics, the film remains alongside The Human Centipede, Cannibal Holocaust, and others, as examples of how filmmakers push the limits of what is acceptable. A Serbian Film and Cannibal Holocaust are also, not coincidentally, films about filmmaking.

Because films are aimed at mass audiences, they incur censorship controversy in ways that paintings, which can easily be hidden away in private, can usually avoid.

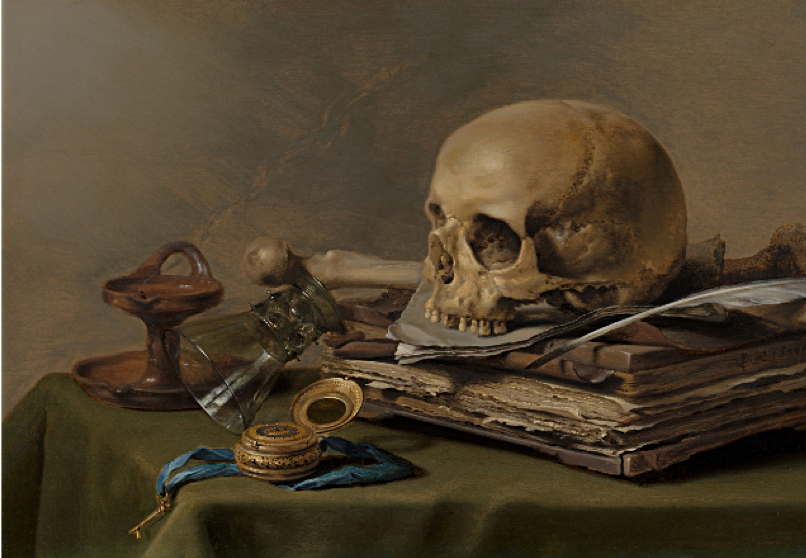

Traces of body horror are evident in the bleeding dead game and slabs of meat of 16 & 17th century Flemish still life, and the highly symbolic skulls in vanitas paintings.

Those pictures were meant to remind the viewer of their own mortality, and that all the things of the earthly world are ultimately in vain. Only God separates us from the butchered pheasant.

In the same way, body horror films also remind us of our own mortality and the vulnerability of the flesh.

Death and the body

A modern perspective on body horror in art is offered by Francis Bacon in Three Studies for a Crucifixion (1962). This is Bacon’s second attempt at a crucifixion scene; the first, painted in 1944, is in the Tate Britain. While the earlier painting shows three barely anthropomorphic monstrous creatures, the 1962 painting explicitly connects the human body to the slaughterhouse, to meat, to the inevitability of death. In fact, Francis Bacon’s whole body of work could be considered an exercise in painting body horror. Critic Adrian Searle notes that “Bacon’s art . . . contains an entire repertoire of bruises, wounds, amputations done up with soiled bandages.” (Adrian Searle, “Painted Screams”, The Guardian, Tuesday, 9th September 2008) Bacon here completely rejects the idea of composed spirituality in death; he also rejects the pretty, romanticized view of death seen in paintings such as the morbid but sentimental Death of Chatterton by Henry Wallis (1856), below, one of the most popular and widely reproduced of Victorian paintings.

©Gillian Mciver 2021 ArtHistoryfilm Art History for Filmmakers. Text not to be reproduced without permission.