Welcome to A History of the World in 16 Paintings. I am going to explain the whole history of the world (well, selected exciting bits of it, anyway) through sixteen extraordinary paintings and then tell you about the films inspired by both the historical story and the picture. Stay tuned for some real surprises.

I will be offering you a preview of an exciting new project that I’m working on, and you are the first to know about it. I’d love to hear what you think. Don’t forget to sign up to my newsletter to get exclusive content from the series.

Who knows, there might be more than 16 … stay tuned

The execution of Lady Jane Grey by Paul Delaroche National Gallery London Fair use applies educational / critique use only. Source: Wikimedia Commons

The Execution of Lady Jane Grey

Paul Delaroche painted this picture in 1833. As a French artist in turbulent political times, it was probably prudent to paint exciting scenes from a distant period of another country’s history. Here he depicts the execution of Jane Grey, a young aristocrat from the Tudor family who was briefly Queen of England.

Jane is sometimes known as the ‘nine days Queen’ because her reign was extraordinarily short. When young King Edward VI died, he apparently named Jane as his heir as the closest legitimate member of the Tudor family who could claim the throne. Edward did have two half-sisters by way of his father, Henry VIII. However, both Mary and Elizabeth were considered illegitimate: Henry had divorced Mary’s mother Catherine of Aragon and executed Elizabeth’s mother Anne Boleyn.

Jane was brought to the throne partly through the machinations of her family, who sought to fulfil their own ambitions through her. However, Mary also had partisans, and after a very short time Mary prevailed. Jane was arrested and thrown in prison as Mary claimed the throne, becoming Mary I. Mary was the first full Queen regnant of England; that is, a Queen who rules entirely in her own right.

Apparently, Mary did not want to execute Jane but it was politically expedient to do so, and so therefore the young girl (only 16 years old!) was taken from her prison in the Tower onto Tower Green and publicly beheaded. If you visit the Tower today, the Beefeater guides will show you exactly where Jane was executed.

However, Delaroche doesn’t show this public beheading. Instead he depicts the action in a dark chamber, so he’s able to manipulate the lighting to make it look even more harrowing. Delaroche wants you, the viewer, to sympathise with Jane: her fragility, purity and innocence emphasised by the flimsy white dress she’s wearing and the pearly luminescence of her skin. At the same time, the picture plays into 19th-century ideas about fragile womanhood and also the titillation of the ‘woman in peril’ trope.

Lady Jane, the movie

In the 1980s, theatre director Trevor Nunn directed a film version of Jane Grey’s story, called Lady Jane with a young Helena Bonham Carter playing Jane (in a wonderful, feisty performance). The film recast Jane and her handsome husband Guilford Dudley as doomed young lovers fighting against a hostile and vaguely Thatcherite establishment. It’s very romantic and good fun; not necessarily accurate but it serves as a good introduction to the Jane and her life, and suggests what it might have been like to live in those fractious Tudor times.

More information

the painting: https://www.nationalgallery.org.uk/paintings/paul-delaroche-the-execution-of-lady-jane-grey

the film: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lady_Jane_(1986_film)

the history: https://www.historic-uk.com/HistoryUK/HistoryofEngland/Lady-Jane-Grey/

Books:

Nicola Tallis, Crown of Blood: The Deadly Inheritance of Lady Jane Grey

Eric Ives, Lady Jane Grey – A Tudor Mystery

and a novel version: Alison Weir, Innocent Traitor

MORE of A History of the World in 16 paintings, and the films they inspired:

Gros’s Battle of Aboukir

Thomas Cole’s The Savage State

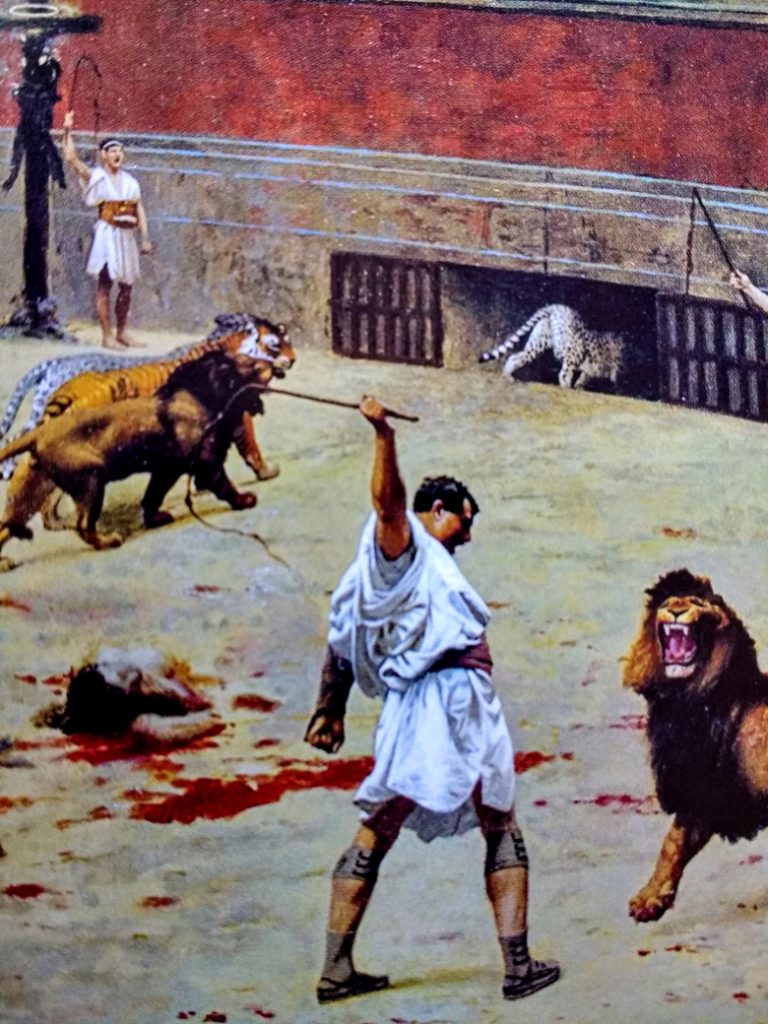

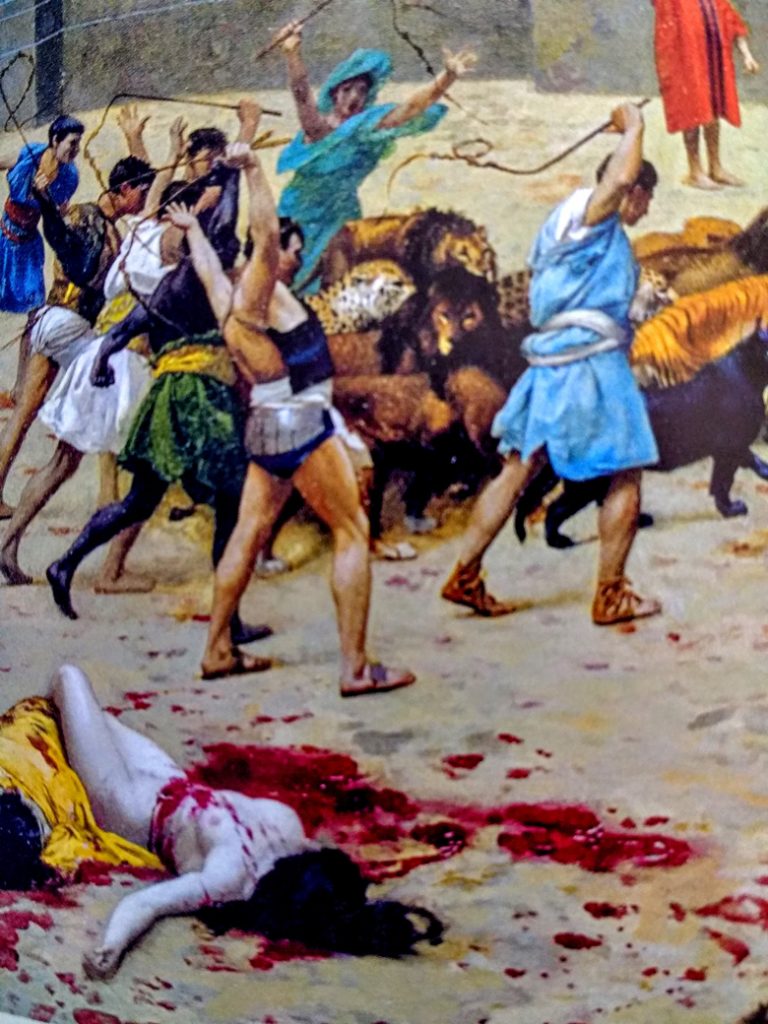

![ean-Léon Gérôme [CLICK IMAGE TO EXPAND] Gathering Up the Lions in the Circus Source: https://www.pubhist.com/w38153](http://arthistoryfilm.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/gerome-lions-1.jpg)

![Giorgione - Three_Philosophers [Google_Art_Project]](http://arthistoryfilm.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/Giorgione_-_Three_Philosophers_-_Google_Art_Project-300x255.jpg)